Introduction

In his acceptance speech for the Test-of-Time award in NeurIPS 2017,1 Ali Rahimi2 started a controversy by frankly declaring (Rahimi 2018, 12’10”). His concerns on the lack of theoretical understanding of machine learning for critical decision-making are rightful:

1 Conference on Neural Information Processing.

2 Research Scientist, Google.

‘We are building systems that govern healthcare and mediate our civic dialogue. We would influence elections. I would like to live in a society whose systems are built on top of verifiable, rigorous, thorough knowledge and not on alchemy.’

The next day, Yann LeCun3 responded:

3 Deep Learning pioneer and 2018 Turing award winner. https://bit.ly/3CQNwTU

‘Criticising an entire community (…) for practising “alchemy”, simply because our current theoretical tools have not caught up with our practice is dangerous.’

Both researchers, at least, agree upon one thing: the practice of machine learning has outpaced its theoretical development. That is certainly a research opportunity.

A Tale of Babylonians and Greeks

Richard Feynman (Figure 1.1) used to lecture this story (Feynman 1994): Babylonians were pioneers in mathematics; Yet, the Greeks took the credit. We are used to the Greek way of doing Math: start from the most basic axioms and build up a knowledge system. Babylonians were quite the opposite; they were pragmatic. No knowledge was considered more fundamental than others, and there was no urge to derive proofs in a particular order. Babylonians were concerned with the phenomena, Greeks with the ordinance. In Feynman’s view, science is constructed in the Babylonian way. There is no fundamental truth. Theories try to connect dots from different pieces of knowledge. Only as science advances, one can worry about reformulation, simplification and ordering. Scientists are Babylonians; mathematicians are Greeks.

Mathematics and science are both tools for knowledge acquisition. They are also social constructs that rely on peer-reviewing. They are somewhat different, however.

Science is empiric, based on facts collected from experience. When physicists around the world measured events that corroborated Newton’s “Law of Universal Gravitation”, they did not prove it correct; they just made his theory more and more plausible. Still, only one experiment was needed to show that Einstein’s Relativity Theory was even more believable. In contrast, we can and do prove things in mathematics.

In mathematics, knowledge is absolute truth, and the way one builds new knowledge with it, its inference method, is deduction. Mathematics is a language, a formal one, a tool to precisely communicate some kinds of thoughts. As it happens with natural languages, there is beauty in it. The mathematician expands the boundaries of expression in this language.

In science, there are no axioms: a falsifiable hypothesis/theory is proposed, and logical conclusions (predictions) from the theory are empirically tested. Despite inferring hypotheses by induction, there is no influence of psychology in the process. A tested hypothesis is not absolute truth. A hypothesis is never verified, only falsified by experiments (Popper 2004, 31–50). Scientific knowledge is belief justified by experience; there are degrees of plausibility.

Understanding the epistemic contrast between mathematics and science will help us understand the past of AI and avoid some perils in its future.

The importance of theoretical narratives

Science is a narrative of how we understand Nature (Gleiser and Sowinski 2018). In science, we collect facts, but they need interpretation. The logical conclusion from the hypothesis that predicts some behaviour in nature gives a plausible meaning to what we observed.

To illustrate, take the ancient human desire of flying. There have always been stories of men strapping wings to themselves and attempting to fly by jumping from a tower and flapping those wings like birds (see Farrington 2016). While concepts like lift, stability, and control were poorly understood, most human flight attempts ended in severe injury or even death. It did not matter how much evidence, how many hours of seeing different animals flying, those ludicrous brave men experienced; the meaning they took from what they saw was wrong, and their predictions incorrect.

They did not die in vain4; Science advances when scientists are wrong. Theories must be falsifiable, and scientists cheer for their failure. When it fails, there is room for new approaches. Only when we understood the observations in animal flight from the aerodynamics perspective, we learned to fly better than any other animal before. Science works by a “natural selection” of ideas, where only the fittest ones survive until a better one is born. Chaitin also points out that an idea has “fertility” to the extent to which it “illuminates us, inspires us with other ideas, and suggests unsuspected connections and new viewpoints” (Chaitin 2006, 9).

4 Those “researchers” deserved, at least, a Darwin Award of Science. The Darwin Award is satirical honours that recognise individuals who have unwillingly contributed to human evolution by selecting themselves out of the gene pool.

Being a Babylonian enterprise, science has no clear path. One of the exciting facts one can learn by studying its history is that robust discoveries have arisen through the study of phenomena in human-made devices (Pierce, n.d.). For instance, Carnot’s first and only scientific work (Klein 1974) gave birth to thermodynamics: the study of energy, the conversion between its different forms, and the ability of energy to do work; the science that explains how steam engines work. However, steam engines came before Carnot’s work and were studied by him. Such human-made devices may present a simplified instance of more complex natural phenomena.

Another example is Information Theory. Several insights of Shannon’s theory of communication were generalisations of ideas already present in Telegraphy (Shannon 1948). New theories in artificial intelligence can, therefore, be developed from insights in the study of deep learning phenomena.5

5 Understanding human intelligence using artificial intelligence is a field of study called Computational Neuroscience.

Bringing science to Computer Science

Despite the name, Computer Science has been more mathematics than science. We, computer scientists, are very comfortable with theorems and proofs, not much with theories.

Nevertheless, AI has essentially become a Babylonian enterprise, a scientific endeavour. Thus, there is no surprise when some computer scientists still see AI with some distrust and even disdain, despite its undeniable usefulness:

Even among AI researchers, there is a trend of “mathiness” and speculation disguised as explanations in conference papers (Lipton and Steinhardt 2018).

There are few venues for papers that describe surprising phenomena without trying to come up with an explanation. As if the mere inconsistency of the current theoretical framework was unworthy of publication.

While physicists rejoice in finding phenomena that contradict current theories, computer scientists get baffled. In Natural Sciences, unexplained phenomena lead to theoretical development. Some believe they bring winters, periods of progress stagnation and lack of funding in AI. This seems to be LeCun’s opinion.6

6 Due to all possible alternative explanations (lack of computational power, no availability of massive datasets), it seems harsh or simply wrong to blame theorists.

Artificial Intelligence has been through several of the aforementioned “winters”. In 1957, Herbert Simon7 famously predicted that within ten years, a computer would be a chess champion (Russell, Norvig, and Davis 2010, sec. 1.3). It took around 40 years, in any case. Computer scientists lacked understanding of the exponential nature of the problems they were trying to solve: Computational Complexity Theory had yet to be invented.

7 Herbert Simon (1916–2001) received the Turing Award in 1975, and the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1978.

Machine Learning Theory (computational and statistical) tries to avoid a similar trap by analysing and classifying learning problems according to the number of samples required to learn them (besides the number of steps). The matter of concern is that it currently predicts that generalisation requires simpler models in terms of parameters. In total disregard to the theory, deep learning models have shown spectacular generalisation power with hundreds of millions of parameters (and even more impressive overfitting capacity ).

Problem

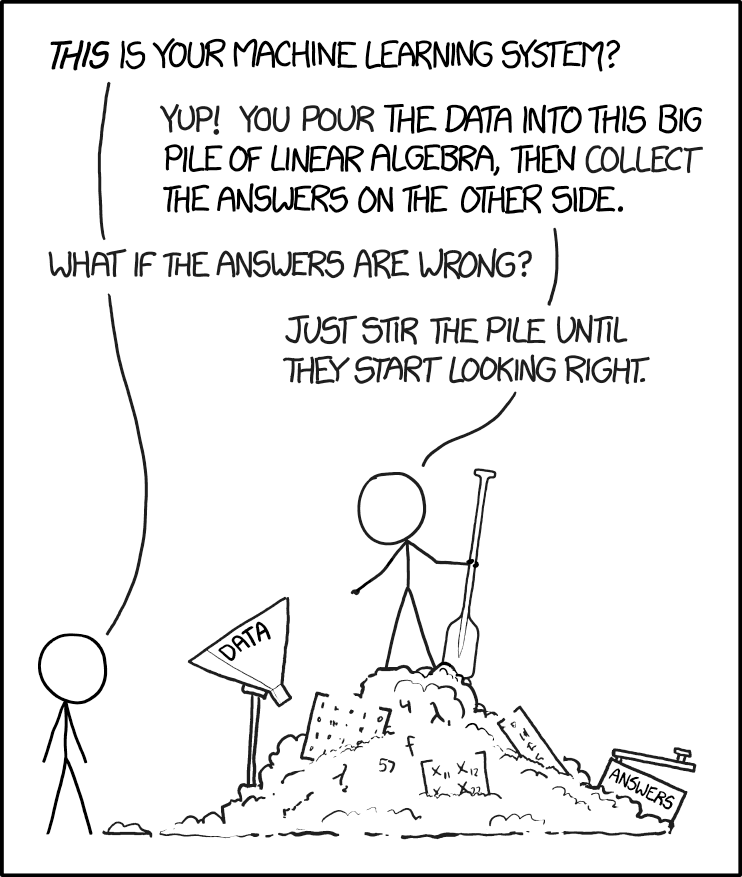

In the last decade, we have witnessed a myriad of astonishing successes in Deep Learning. Despite those many successes in research and industry applications, we may again be climbing a peak of inflated expectations. If in the past, the false solution was to “add computation power” on problems, today we try to solve them by “piling data” (Figure 1.2). Such behaviour has triggered a winner-takes-all competition for who collects more data (our data) amidst a handful of large corporations, raising ethical concerns about privacy and concentration of power (O’Neil 2016).

Nevertheless, we know that learning from way fewer samples is possible: humans show a much better generalisation ability than our current state-of-the-art artificial intelligence. To achieve such needed generalisation power, we may need to understand better how learning happens in deep learning. Rethinking generalisation might reshape the foundations of machine learning theory (Zhang et al. 2016).

Possible new explanation in the horizon

In 2015, Tishby and Zaslavsky (2015) proposed a theory of deep learning (Tishby and Zaslavsky 2015) based on the information-theoretical concept of the bottleneck principle, of which Tishby is one of the authors. Later, in 2017, Shwartz-Ziv and Tishby (2017) followed up on the IBT with the paper , which was presented in a well-attended workshop8, with appealing visuals that clearly showed a “phase transition” happening during training. The video posted on Youtube (Tishby 2017) became a “sensation”9, and received a wealth of publicity when well-known researchers like Geoffrey Hinton10, Samy Bengio (Apple) and Alex Alemi (Google Research) have expressed interest in Tishby’s ideas (Wolchover 2017). they are called formal languages.

8 Deep Learning: Theory, Algorithms, and Applications. Berlin, June 2017 http://doc.ml.tu-berlin.de/dlworkshop2017

9 By the time of this writing, this video as more than 84,000 views, which is remarkable for an hour-long workshop presentation in an academic niche. https://youtu.be/bLqJHjXihK8

10 Another Deep Learning Pioneer and Turing award winner (2018).

‘I believe that the information bottleneck idea could be very important in future deep neural network research.’ — Alex Alemi

Andrew Saxe (Harvard University) rebutted Shwartz-Ziv and Tishby (2017) claims in and was followed by other critics. According to Saxe, it was impossible to reproduce (Shwartz-Ziv and Tishby 2017)’s experiments with different parameters.

Has the initial enthusiasm on the IBT been unfounded? Have we let us “fool ourselves” by beautiful charts and a good story?

Problem statement

The practice of modern machine learning has outpaced its theoretical development. In particular, deep learning models present generalisation capabilities unpredicted by the current machine learning theory. There is yet no established new general theory of learning which handles this problem.

IBT was proposed as a possible new theory with the potential of filling the theory-practice gap. Unfortunately, to the extent of our knowledge, there is still no comprehensive digest of IBT nor an analysis of how it relates to current MLT.

Objective

This dissertation aims to investigate to what extent can the emergent Information Bottleneck Theory help us better understand Deep Learning and its phenomena, especially generalisation, presenting its strengths, weaknesses and research opportunities.

Research Questions

- What are the fundamentals of IBT? How do they differ from the ones from MLT?

- What is the relationship between IBT and current MLT? How different or similar they are?

- Is IBT capable of explaining the phenomena MLT already explains?

- Does IBT invalidate results in MLT?

- Is IBT capable of explaining phenomena still not well understood by MLT?

- What are Information Bottleneck Theory’s (IBT) strengths?

- What are Information Bottleneck Theory’s (IBT) weaknesses?

- What has been already developed in IBT?

- What are Information Bottleneck Theory’s (IBT) research opportunities?

Methodology

Given that IBT is yet not a well-established learning theory, there were two difficulties that the research had to address:

There is a growing interest in the subject, and new papers are published every day. It was essential to select literature and restrain the analysis.

Early on, the marks of an emergent theory in its infancy manifested in the form of missing assumptions, inconsistent notation, borrowed jargon, and seeming missing steps. Foremost, it was unclear what was missing from the theory and what was missing in our understanding.

An initial literature review on IBT was conducted to define the scope.11 We then chose to narrow the research to theoretical perspective on generalisation, where we considered that it could bring fundamental advances. We made the deliberate choice of going deeper in a limited area of IBT and not broad, leaving out a deeper experimental and application analysis, all the work on ITL12 (Principe 2010) and statistical-mechanics-based analysis of SGD (P. Chaudhari and Soatto 2018; Pratik Chaudhari et al. 2019). From this set of constraints, we chose a list of pieces of IBT literature to go deeper.

In order to answer , we discuss the epistemology of AI to choose fundamental axioms (definition of intelligence and the definition of knowledge) with which we deduced from the ground up MLT, IT and IBT, revealing hidden assumptions, pointing out similarities and differences. By doing that, we built a “genealogy” of these research fields. This comparative study was essential for identifying missing gaps and research opportunities.

In order to answer , we first dissected the selected literature ([[ch:literature]][3]) and organised scattered topics in a comprehensive sequence of subjects.

In the process of the literature digest, we identified results, strengths, weaknesses and research opportunities.

11 Not even the term IBT is universally adopted.

12 ITL makes the opposite path we are taking, bringing concepts of machine learning to information theory problems.

Contributions

In the research conducted, we produced three main results that, to the extent of our knowledge, are original:

The dissertation itself is the main expected result: a comprehensive digest of the IBT literature and a snapshot analysis of the field in its current form, focusing on its theoretical implications for generalisation.

We propose an Information-Theoretical learning problem different from MDL proposed by (Hinton and Van Camp 1993) for which we derived bounds using Shannon’s . These results, however, are only indicative as they lack peer review to be validated.

We present a critique on Achille (2019)’s explanation (Achille 2019; Achille and Soatto 2018) for the role of layers in Deep Representation in the IBT perspective (?sec-achille_proof_critique), pointing out a weakness in the argument that, as far as we know, has not yet been presented. We then propose a counter-intuitive hypothesis that layers reduce the model’s “effective” hypothesis space. This hypothesis is not formally proven in the present work, but we try to give the intuition behind it (?sec-proposed_hypothesis). This result has not yet been validated as well.

Dissertation preview and outline

The dissertation is divided into two main parts (Background and The emergence of a theory), with a break in the middle (Intermezzo).

Background

Chapter 2 — Artificial Intelligence: The chapter defines what artificial intelligence is, presents the epistemological differences of intelligent agents in history, and discusses their consequences to machine learning theory.

Chapter 3 — Probability Theory: The chapter derives propositional calculus and probability theory from a list of desired characteristics for epistemic agents. It also presents basic Probability Theory concepts.

Chapter 4 — Machine Learning Theory: The chapter presents the theoretical framework of Machine Learning, the PAC model, theoretical guarantees for generalisation, and expose its weaknesses concerning Deep Learning phenomena.

Chapter 5 — Information Theory: The chapter derives Shannon Information from Probability Theory, explicates some implicit assumptions, and explains basic Information Theory concepts.

Intermezzo

- Chapter 6 — Information-Theoretical Epistemology: This chapter closes the background part and opens the IBT part of the dissertation. It shows the connection of IT and MLT in the learning problem, proves that Shannon theorems can be used to prove PAC bounds and present the MDL Principle, an earlier example of this kind of connection.

The emergence of a theory

Chapter 7 — IB Principle: Explains the IB method and its tools: KL as a natural distortion (loss) measure, the IB Lagrangian and the Information Plane.

Chapter 8 — IB and Representation Learning: Presents the learning problem in the IBT perspective (not specific to DL). It shows how some usual choices of the practice of DL emerge naturally from a list of desired properties of representations. It also shows that the information in the weights bounds the information in the activations.

Chapter 9 — IB and Deep Learning: This chapter presents the IBT perspective specific to Deep Learning. It presents IBT analysis of Deep Learning training, some examples of applications of IBT to improve or create algorithms; and the IBT learning theory of Deep Learning. We also explain Deep Learning phenomena in the IBT perspective.

Chapter 10 — Conclusion: In this chapter, we present a summary of the findings, answer the research questions, and present suggestions for future work.

We found out that IBT does not invalidate MLT; it just interprets complexity not as a function of the data (number of parameters) but as a function of the information contained in the data. With this interpretation, there is no paradox in improving generalisation by adding layers.

Furthermore, they both share more or less the same “genealogy” of assumptions. IBT can be seen as particular case of MLT. Nevertheless, IBT allows us to better understand the training process and provide a different narrative that helps us comprehend Deep Learning phenomena in a more general way.