Artificial Intelligence

This chapter defines artificial intelligence, presents the epistemological differences of intelligent agents in history, and discusses their consequences to machine learning theory.

What is Artificial Intelligence?

Definition 2.1 AI is the branch of Computer Science that studies general principles of intelligent agents and how to construct them (Russell, Norvig, and Davis 2010).

This definition uses the terms intelligence and intelligent agents, so let us start from them.

What is intelligence?

Despite a long history of research, there is still no consensual definition of intelligence.1 Whatever it is, though, humans are particularly proud of it. We even call our species homo sapiens, as intelligence was an intrinsic human characteristic.

1 For a list with 70 definitions of intelligence, see Legg and Hutter (2007).

In this dissertation:

Definition 2.2 Intelligence is the ability to predict a course of action to achieve success in specific goals.

Intelligent Agents

Under our generous definition, intelligence is not limited to humans. It applies to any agent2: animal or machine. For example, a bacteria can perceive its environment through chemical signals, process them, and then produce chemicals to signal other bacteria. An air-conditioning can observe temperature changes, know its state, and adapt its functioning, turning off if it is cold or on if it is hot — intelligence exempts understanding. The air-conditioning does not comprehend what it is doing. The same way a calculator does not know arithmetics.

2 An agent is anything that perceives its environment and acts on it.

A strange inversion of reasoning

This competence without comprehension is what the philosopher Daniel Dennett calls Turing’s strange inversion of reasoning3. The idea of a strange inversion comes from one of Darwin’s 19th-century critics Dennett (2009):

3 In his work, Turing discusses if computers can “think”, meaning to examine if they can perform indistinguishably from the way thinkers do.

‘In the theory with which we have to deal, Absolute Ignorance is the artificer; so that we may enunciate as the fundamental principle of the whole system, that, in order to make a perfect and beautiful machine, it is not requisite to know how to make it. This proposition will be found, on careful examination, to express, in condensed form, the essential purport of the [Evolution] Theory, and to express in a few words all Mr Darwin’s meaning; who, by a strange inversion of reasoning, seems to think Absolute Ignorance fully qualified to take the place of Absolute Wisdom in all of the achievements of creative skill.’

— Robert MacKenzie

Counterintuitively to MacKenzie (1868) and many others to this date, intelligence can emerge from absolute ignorance. Turing’s strange inversion of reasoning comes from the realisation that his automata can perform calculations by symbol manipulation, proving that it is possible to build agents that behave intelligently, even if they are entirely ignorant of the meaning of what they are doing (Turing 2007).

Dreaming of robots

From mythology to Logic

The idea of creating an intelligent agent is perhaps as old as humans. There are accounts of artificial intelligence in almost any ancient mythology: Greek, Etruscan, Egyptian, Hindu, Chinese (Mayor 2018). For example, in Greek mythology, the story of the bronze automaton of Talos built by Hephaestus, the god of invention and blacksmithing, first mentioned around 700 BC.

This interest may explain why, since ancient times, philosophers have looked for mechanical methods of reasoning. Chinese, Indian and Greek philosophers all developed formal deduction in the first millennium BC.In particular, Aristotelian syllogism, laws of thought, provided patterns for argument structures to yield irrefutable conclusions, given correct premises. These ancient developments were the beginning of the field we now call Logic.

Rationalism: The Cartesian view of Nature

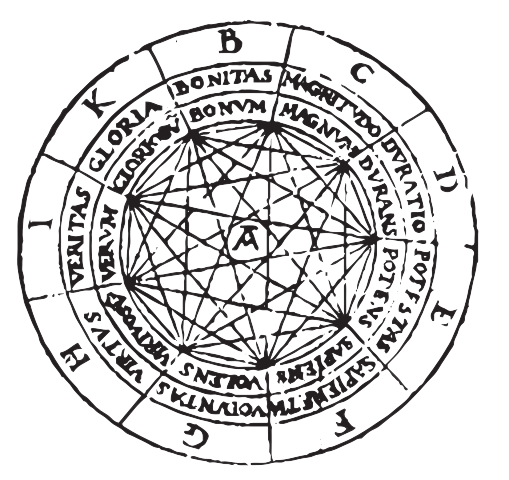

Example of Lull’s Ars Magna’s paper discs.

In the 13th century, the Catalan philosopher Ramon Lull wanted to produce all statements the human mind can think. For this task, he developed logic paper machines, discs of paper filled with esoteric coloured diagrams that connected symbols representing statements. Unfortunately, according to Gardner (1959), in a modern reassessment of his work, “it is impossible, perhaps, to avoid a strong sense of anticlimax”. With megalomaniac self-esteem that suggests psychosis, his delusional sense of importance is more characteristic of cult founders. On the bright side, his ideas and books exerted some magic appeal that helped them be rapidly disseminated through all Europe.

Lull’s work greatly influenced Leibniz and Descartes, who, in the 17thcentury, believed that all rational thought could be mechanised. This belief was the basis of rationalism, the epistemic view of the Enlightenment that regarded reason as the sole source of knowledge. In other words, they believed that reality has a logical structure and that certain truths are self-evident, and all truths can be derived from them.

There was considerable interest in developing artificial languages during this period. Nowadays, they are called formal languages.

‘If controversies were to arise, there would be no more need for disputation between two philosophers than between two accountants. For it would suffice to take their pencils in their hands, to sit down to their slates, and to say to each other: Let us calculate.’

— Gottfried Leibniz

The rationalist view of the world has had an enduring impact on society until today. In the 19thcentury, George Boole and others developed a precise notation for statements about all kinds of objects in Nature and their relations. Before them, Logic was philosophical rather than mathematical. The name of Boole’s masterpiece, “The Laws of Thought”, is an excellent indicator of his Cartesian worldview.

At the beginning of the 20th century, some of the most famous mathematicians, David Hilbert, Bertrand Russel, Alfred Whitehead, were still interested in formalism: they wanted mathematics to be formulated on a solid and complete logical foundation. In particular, Hilbert’s Entscheidungs Problem (decision problem) asked if there were limits to mechanical Logic proofs (Chaitin 2006).

Kurt Gödel’s incompleteness theorem (1931) proved that any language expressive enough to describe arithmetics of the natural numbers is either incomplete or inconsistent. This theorem imposes a limit on logic systems. There will always be truths that will not be provable from within such languages: there are “true” statements that are undecidable.

Alan Turing brought a new perspective to the Entscheidungs Problem: a function on natural numbers that an algorithm in a formal language cannot represent cannot be computable (Chaitin 2006). Gödel’s limit appears in this context as functions that are not computable, no algorithm can decide whether another algorithm will stop or not (the halting problem). To prove that, Turing developed a whole new general theory of computation: what is computable and how to compute it, laying out a blueprint to build computers, and making possible Artificial Intelligence research as we know it. An area in which Turing himself was very much invested.

Empiricism: The sceptical view of Nature

The response to rationalism was empiricism, the epistemological view that knowledge comes from sensory experience, our perceptions of the world. Locke explains this with the peripatetic axiom4: “there is nothing in the intellect that was not previously in the senses” (Uzgalis 2020). Bacon, Locke and Hume were great exponents of this movement, which established the grounds of the scientific method.

4 This citation is the principle from the Peripatetic school of Greek philosophy and is found in Thomas Aquinas’ work cited by Locke.

David Hume, in particular, presented in the 18th century a radical empiricist view: reason only does not lead to knowledge. In (Hume 2009), Hume distinguishes relations of ideas, propositions that derive from deduction and matters of facts, which rely on the connection of cause and effect through experience (induction). Hume’s critiques, known as the Problem of Induction, added a new slant on the debate of the emerging scientific method.

From Hume’s own words:

‘The bread, which I formerly eat, nourished me; that is, a body of such sensible qualities was, at that time, endued with such secret powers: but does it follow, that other bread must also nourish me at another time, and that like sensible qualities must always be attended with like secret powers? The consequence seems nowise necessary.’

— David Hume

There is no logic to deduce that the future will resemble the past. Still, we expect uniformity in Nature. As we see more examples of something happening, it is wise to expect that it will happen in the future just as it did in the past. There is, however, no rationality5 in this expectation.

5 In the philosophical sense.

Hume explains that we see conjunction repeatedly, “bread” and “nourish”, and we expect uniformity in Nature; we hope that “nourish” will always follow “eating bread”; When we fulfil this expectancy, we misinterpret it as causation. In other words, we project causation into phenomena. Hume explained that this connection does not exist in Nature. We do not “see causation”; we create it.

This projection is Hume’s strange inversion of reasoning (Huebner 2017): We do not like sugar because it is sweet; sweetness exists because we like (or need) it. There is no sweetness in honey. We wire our brain so that glucose triggers a labelled desire we call sweetness. As we will see later, sweetness is information. This insight shows the pattern matching nature of humans. Musicians have relied on this for centuries. Music is a sequence of sounds in which we expect a pattern. The expectancy is the tension we feel while the chords progress. When the progression finally resolves, forming a pattern, we release the tension. We feel pattern matching in our core. It is very human, it can be beneficial and wise, but it is, stricto sensu, irrational.

The epistemology of the sceptical view of Nature is science: to weigh one’s beliefs to the evidence. Knowledge is not absolute truth but justified belief. It is a Babylonian epistemology.

In rationalism, Logic connects knowledge and good actions. In empiricism, the connection between knowledge and justifiable actions is determined by probability. More specifically, Bayes’ theorem. As Jaynes puts it, probability theory is the “Logic of Science” . 6

6 The Bayes’ theorem is attributed to the Reverend Thomas Bayes after the posthumous publication of his work. By the publication time, it was an already known theorem, derived by Laplace.

The birth of AI as a research field

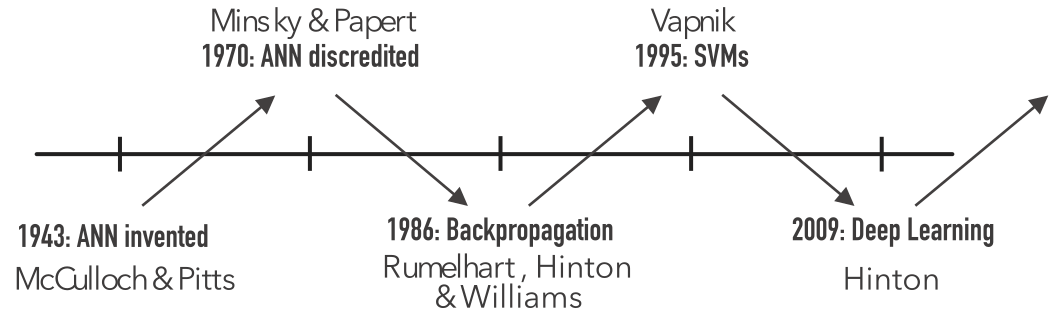

In 1943, McCulloch and Pitts, a neurophysiologist and a logician, demonstrated that neuron-like electronic units could be wired together, act and interact by physiologically plausible principles and perform complex logical calculations (Russell, Norvig, and Davis 2010). Moreover, they showed that any computable function could be computed by some network of connected neurons (McCulloch and Pitts 1943). Their work marks the birth of ANNs, even before the field of AI had this name. It was also the birth of Connectionism, using artificial neural networks, loosely inspired by biology, to explain mental phenomena and imitate intelligence.

Their work inspired John von Neumann’s demonstration of how to create a universal Turing machine out of electronic components, which lead to the advent of computers and programming languages. Ironically, these advents hastened the ascent of the formal logicist approach called Symbolism, disregarding Connectionism.

In 1956, John McCarthy, Claude Shannon (who invented Information Theory, Figure 2.1), Marvin Minsky and Nathaniel Rochester organised a 2-month summer workshop in Dartmouth College to bring researchers of different fields concerned with “thinking machines” (cybernetics, information theory, automata theory). The workshop attendees became a community of researchers and chose the term “artificial intelligence” for the field.

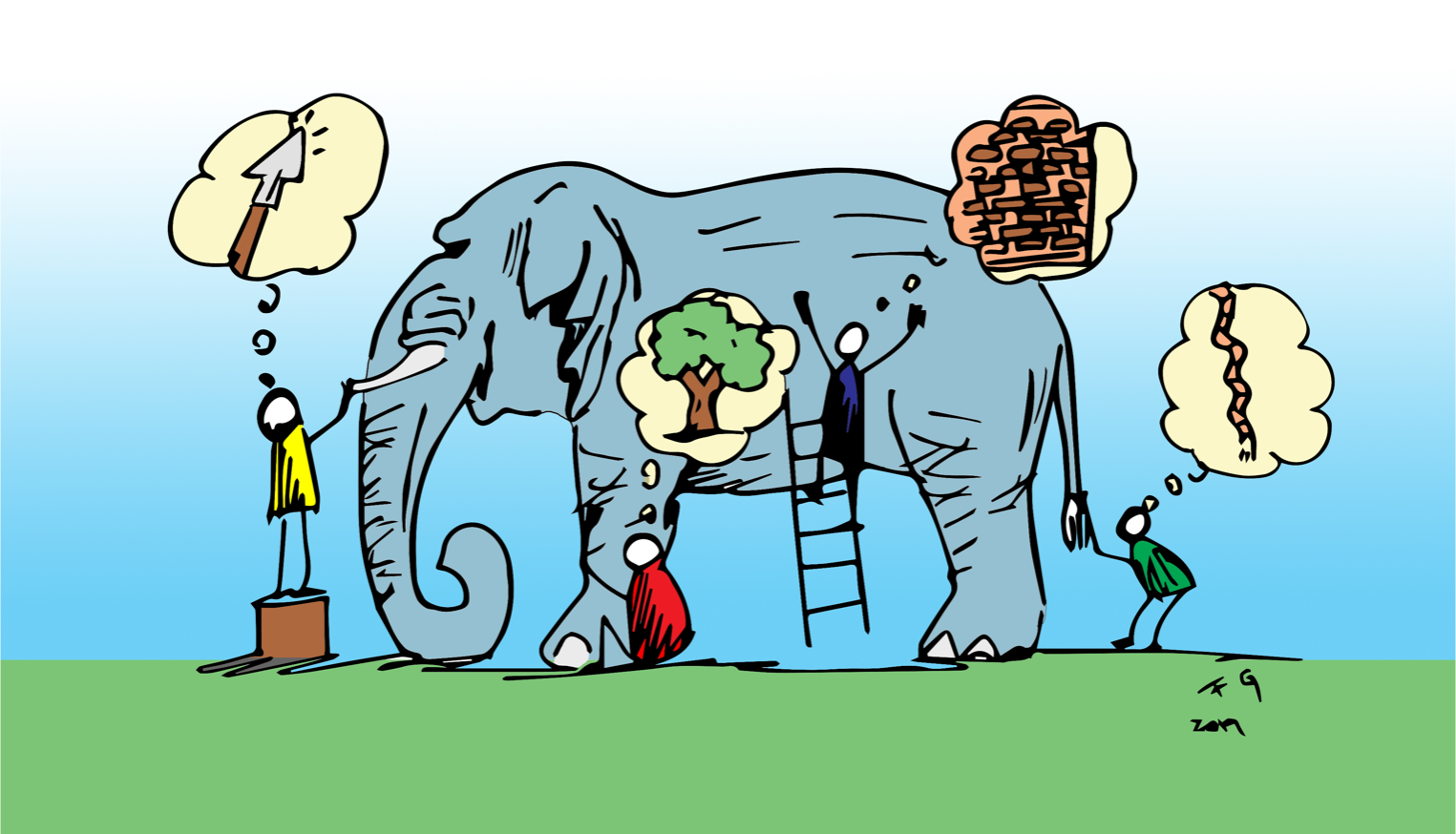

It was six men of Indostan

To learning much inclined,

Who went to see the Elephant

(Though all of them were blind),

That each by observation

Might satisfy his mind

—John Godfrey Saxe,

The Blind Men and the Elephant

Building Intelligent Agents

Anatomy of intelligent agents

Like the blind men in the parable, an intelligent agent shall model her understanding of Nature from limited sensory data.

The expected result of this conversation is a change in the agent’s KB, therefore in her model and, more importantly, her future decisions. The model is an abstraction of how the agent “thinks” the world is (her “mental picture” of the environment). Therefore, it should be consistent with it: if something is true in Nature, it is equally valid, mutatis mutandis, in the model. A Model should also be as simple as possible so that the agent can make decisions that maximise a chosen performance measure, but not simpler. As the agent knows more about Nature, less it gets surprised by it.

This rudimentary anatomy is flexible enough to entail different epistemic views, like the rationalist (mathematical) and the empiricist (scientific); different approaches to how to implement the knowledge base (it can be learned, therefore updatable, or it can be set in stone from an expert prior knowledge); and also from how to implement it (a robot or software).

Noteworthy, though, is that the model that transforms input data into decisions should be the target of our focus.

Symbolism

Symbolism is the pinnacle of rationalism. In the words of Thomas Hobbes, one of the forerunners of rationalism, “thinking is the manipulation of symbols and reasoning is computation”. Symbolism is the approach to building intelligent agents that does just that. It attempts to represent knowledge with a formal language and explicitly connects the knowledge with actions. It is competence from comprehension. In other words, it is programmed.

Even though McCulloch and Pitts work on artificial neural networks predates Von Neumann’s computers, Symbolism dominated AI until the \(1980\)s. It was so ubiquitous that symbolic AI is even called “good old fashioned AI” (Russell, Norvig, and Davis 2010).

The symbolic approach can be traced back to Nichomachean Ethics (Aristotle 2000):

‘We deliberate not about ends but means. For a doctor does not deliberate whether he shall heal, nor an orator whether he shall persuade, nor a statesman whether he shall produce law and order, nor does anyone else deliberate about his end. They assume the end and consider how and by what means it is to be attained; and if it seems to be produced by several means, they consider by which it is most easily and best produced, while if it is achieved by one only they consider how it will be achieved by this and by what means this will be achieved, till they come to the first cause, which in the order of discovery is last.’

— Aristotle

This perspective is so entrenched that Russell, Norvig, and Davis (2010, 7) still says: “(\(\ldots\)) Only by understanding how actions can be justified can we understand how to build an agent whose actions are justifiable”; even though, in the same book, they cover machine learning (which we will address later in this chapter) without noticing it is proof that there are other ways to build intelligent agents. Moreover, it is also a negation of competence without comprehension. It seems that even for AI researchers, the strange inversion of reasoning is uncomfortable ([[ch:introduction]][3]).

All humans, even those in prisons and under mental health care, think their actions are justifiable. Is that not an indication that we rationalise our actions ex post facto? We humans tend to think our rational assessments lead to actions, but it is also likely possible that we act and then rationalise afterwards to justify what we have done, fullheartedly believing that the rationalisation came first.

Claude Shannon’s Theseus

After writing what is probably the most important master’s dissertation of the 20th century and “inventing” IT, what made possible the Information Age we live in today, Claude Shannon enjoyed the freedom to pursue any interest to which his curious mind led him (Soni and Goodman 2017). In the \(1950\)s, his interest shifted to building artificial intelligence. He was not a typical academic, in any case. A lifelong tinkerer, he liked to “think” with his hand as much as with his mind. Besides developing an algorithm to play chess (when he even did not have a computer to run it), one of his most outstanding achievements in AI was Theseus, a robotic maze-solving mouse.7

7 Many AI students will recognise in Theseus the inspiration to Russel and Norvig’s Wumpus World.

To be more accurate, Theseus was just a bar magnet covered with a sculpted wooden mouse with copper whiskers; the maze was the “brain” that solved itself (Klein 2018).

‘Under the maze, an electromagnet mounted on a motor-powered carriage can move north, south, east, and west; as it moves, so does Theseus. Each time its copper whiskers touch one of the metal walls and complete the electric circuit, two things happen. First, the corresponding relay circuit’s switch flips from “on” to “off,” recording that space as having a wall on that side. Then Theseus rotates \(90^{\circ}\) clockwise and moves forward. In this way, it systematically moves through the maze until it reaches the target, recording the exits and walls for each square it passes through.’

— Martin Klein

Symbolic AI problems

Several symbolic AI projects sought to hard-code knowledge about domains in formal languages, but it has always been a costly, slow process that could not scale.

Anyhow, by \(1965\), there were already programs that could solve any solvable problem described in logical notation (Russell, Norvig, and Davis 2010, 4). However, hubris and lack of philosophical perspective made computer scientists believe that “intelligence was a problem about to be solved8.”

8 Marvin Minsky, head of the artificial intelligence laboratory at MIT (\(1967\))

Those inflated expectations lead to disillusionment and funding cuts9 (Russell, Norvig, and Davis 2010). They failed to estimate the inherent difficulty in slating informal knowledge in formal terms: the world has many shades of grey. Besides, complexity theory had yet to be developed: they did not count on the exponential explosion of their problems.

9 Sometimes called winters.

Connectionism: a different approach

The fundamental idea in Connectionism is that intelligent behaviour emerges from a large number of simple computational units when networked together (Goodfellow, Bengio, and Courville 2016).

It was pioneered by McCulloch and Pitts in 1943 (McCulloch and Pitts 1943). One of Connectionism’s first wave developments was Frank Rosenblatt’s Perceptron, an algorithm for learning binary classifiers, or more specifically threshold functions:

\[\begin{align} y= \begin{cases} 1 \text{ if } \mW\vx + \vb > 0\\ 0 \text{ otherwise } \end{cases} \end{align}\]

where \(\mW\) is the vector of weights, \(\vx\) is the input vector, \(\vb\) is a bias, and \(\vy\) is the classification. In neural networks, a perceptron is an artificial neuron using a step function as the activation function.

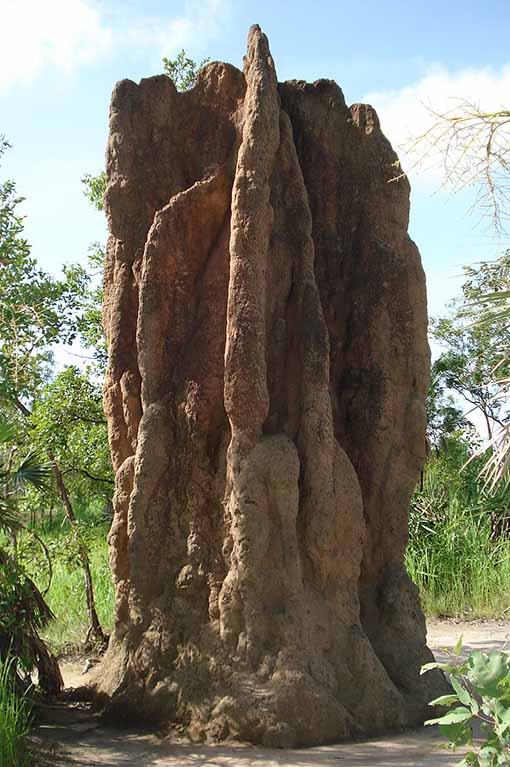

See Figure 2.4, termites self-cooling mounds keep the temperature inside at exactly \(31^{\circ} C\), ideal for their fungus-farming; while the temperatures outside range from 2 to \(40^{\circ} C\) throughout the day. Such building techniques inspired architect Mike Pearce to design a shopping mall that uses a tenth of the energy used by a conventional building of the same size.

From where does termites intelligence come?

‘Individual termites react rather than think, but at a group level, they exhibit a kind of cognition and awareness of their surroundings. Similarly, in the brain, individual neurons do not think, but thinking arises in their connections.’

— Radhika Nagpal, Harvard University (Margonelli 2016).

Such collective intelligence happens in groups of just a couple of million termites. There are around 80 to 90 billion neurons in the human brain, each less capable than a termite, but collectively they show incomparable intelligence capabilities.

In contrast with the symbolic approach, in neural networks, the knowledge is not explicit in symbols but implicit in the strength of the connections between the neurons. Besides, it is a very general and flexible approach since these connections can be updated algorithmically: they are algorithms that learn: the connectionist approach is an example of what we now call Machine Learning.

Machine Learning

Look at Figure 2.5. Is this a picture of a cat? How to write a program to do such a simple classification task (cat/no cat)? One could develop clever ways to use features from the input picture and process them to guess. Though, it is not an easy program to design. Worse, even if one manages to program such a task, how much would it worth to accomplish a related task, to recognise a dog, for example? For long, this was the problem of researchers in many areas of interest of AI:CV, NLP, Speech Recognition SR; much mental effort was put, with inferior results, in problems that we humans solve with apparent ease.

The solution is an entirely different approach for building artificial intelligence: instead of making the program do the task, build the program that outputs the program that does the task. In other words, learning algorithms use “training data” to infer the transformations to the input that generates the desired output.

Types of learning

Machine Learning can happen in different scenarios, which differ in the availability of training data, how training data is received, and how the test data is used to evaluate the learning. Here, we describe the most typical of them (Mohri, Rostamizadeh, and Talwalkar 2012):

Supervised learning: The most successful scenario. The learner receives a set of labelled examples as training data and makes predictions for unseen data.

Unsupervised learning: The learner receives unlabelled training data and makes predictions for unseen instances.

Semi-supervised learning: The learner receives a training sample consisting of labelled and unlabelled data and makes predictions for unseen examples. Semi-supervised learning is usual in settings where unlabelled data is easily accessible, but labelling is too costly.

Reinforcement learning: The learner actively interacts with the environment and receives an immediate reward for her actions. The training and testing phases are intermixed.

Deep Learning

The 2010s have been an AI Renaissance not only in academia but also in the industry. Such successes are mostly due to DL, in particular, supervised deep learning with vast amounts of data trained in GPUs. It was the decade of DL.

‘Deep learning algorithms seek to exploit the unknown structure in the input distribution to discover good representations, often at multiple levels, with higher-level learned features defined in terms of lower-level features.’

— Joshua Bengio (Bengio 2012)*

The name is explained by Goodfellow, Bengio, and Courville (2016): “A graph showing the concepts being built on top of each other is a deep graph. Therefore the name, deep learning” (Goodfellow, Bengio, and Courville 2016). Although it is a direct descendant of the connectionist movement, it goes beyond the neuroscientific perspective in its modern form. It is more a general principle of learning multiple levels of compositions.

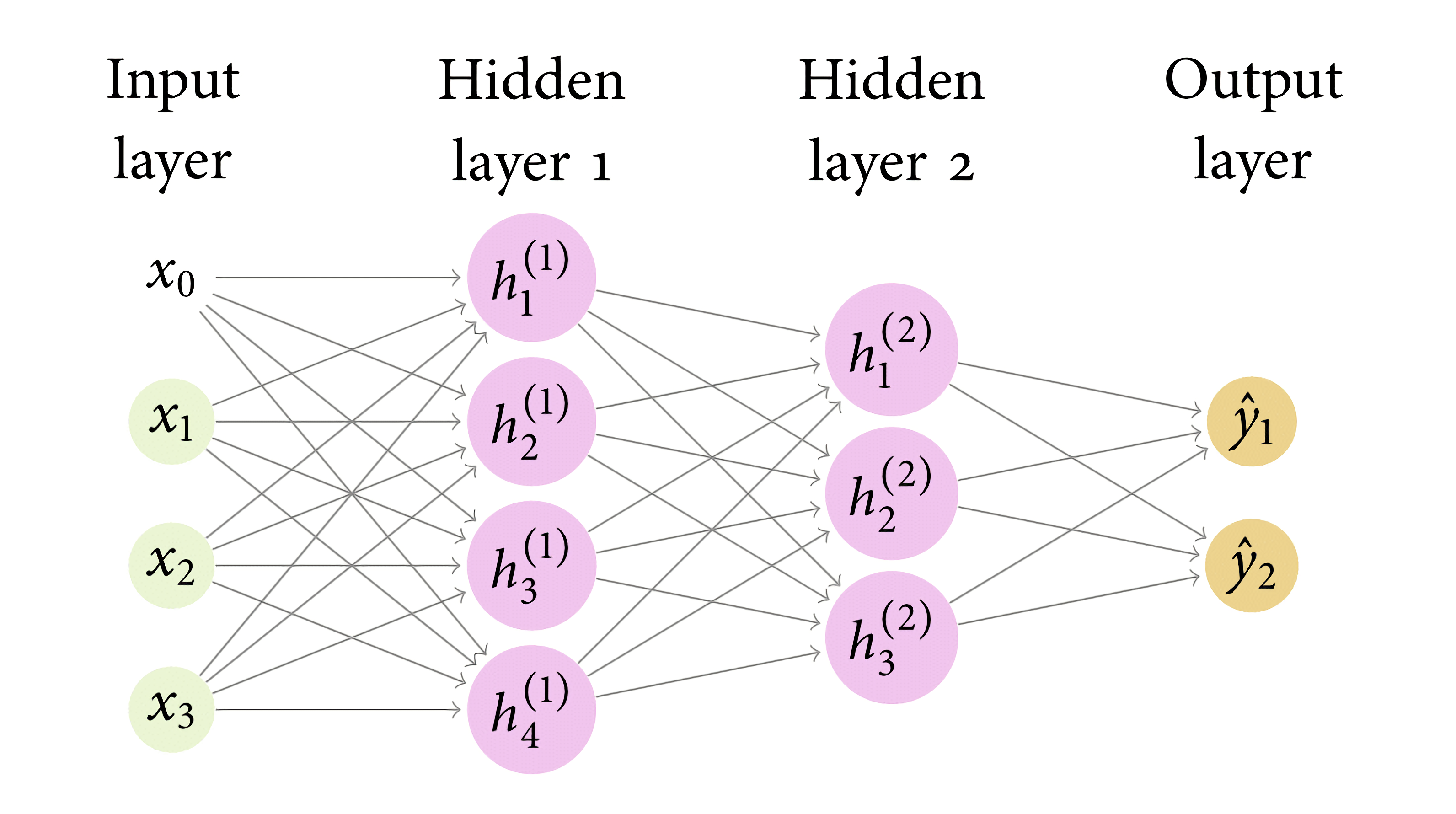

The quintessential example of a deep learning model is the deep feedforward network or MLP (Russell, Norvig, and Davis 2010).

Definition 2.3 Let,

\({\vx}\) be the input vector \(\{\vx_1, \ldots, \vx_m\}\)

\(k\) be the layer index, such that \(k \in [1,l]\),

\(\mW^{(k)}_{i,j}\)be the matrix of weights in the \(k\)-th layer, where \(i \in [0,d_{k-1}], j \in [1, d_k] \text{ and }\mW^{(k)}_{0,:}\) are the biases

\(\sigma\) be a nonlinear function,

a MLPs is a neural network where the input is defined by:

\[ \begin{aligned} h^{(0)}= 1\frown \vx \end{aligned} \]

a hidden layer is defined by:

\[ \begin{aligned} h^{(k)}&=\sigma^{(k)}(\mW^{(k)~\top} h^{(k-1)}). \end{aligned} \]

The output is defined by: \[ \begin{aligned} \hat{y}&=h^{(l)}. \end{aligned} \]

Deep Learning is usually associated with DNNs, but the network architecture is only one of its components:

DNN architecture

SGD — the optimiser

Dataset

Loss function

The architecture is not the sole component essential to current Deep Learning success. The SGD plays a crucial role, and so does the usage of large datasets.

A known problem, though, is that DNNs are prone to overfitting ([[sec:bias-variance]][6]). Zhang et al. (2016) show state-of-the-art convolutional deep neural networks can easily fit a random labelling of training data (Zhang et al. 2016).

Concluding Remarks

This chapter derived the need for a language from the definitions of intelligence and intelligent agents. An intelligent agent needs language to store her knowledge (what she has learned) and with that to communicate/share this knowledge with its future self and with other agents.

We claim (without proving) that a language can be derived from a definition of knowledge: an epistemic choice. We claim that mathematics and science can be seen as languages that differ in consequence of different views on what knowledge is and gave historical background on two epistemic views, Rationalism and Empiricism (Section 2.2.2,Section 2.2.3).

We gave historical background on AI and showed that different epistemic views relate to AI movements: Symbolism and Connectionism. We gave some background on basic AI concepts: intelligent agents, machine learning, types of learning, neural networks and deep learning, showing that DL relates to Connectionism and, hence, to science and an empiricist epistemology. Previously (?sec-bringing_science), we have discussed that Computer Science generally relates to the rationalist epistemology. We hope this can help us better understand our research community.

Assumptions

A definition of intelligence Definition 2.2

An epistemic choice on the definition of Knowledge Section 2.2.2